James J. Coogan was a furniture man. Furniture men were not held in high esteem among the working class of 19th-Century New York City but were viewed as a necessary evil. Perfectly happy to fill your home with beds, tables and chairs sold on “easy terms,” the furniture man was just as happy to show up suddenly and cart them all away again should you miss a single installment. It is perhaps then understandable why Luke Jordan would sing in his 1927 song “Cocaine Blues,” If it ever was a devil born without any horns, it must’ve been the furniture man.

James J. Coogan was a furniture man, and a wealthy one at that. From his operation on the Bowery he amassed a considerable fortune selling (and reselling) furniture to the residents of the Lower East Side. His marriage to Harriet Lynch, daughter of the prosperous landowner William Lynch, brought valuable Hamilton Heights real estate under his control. By 1886, Coogan felt he had suitable stature to be a viable candidate for mayor.

Coogan first courted the endorsement of the Committe of 100 of the Citizens’ Association, a non-partisan group nominally dedicated to better city government. Coogan, along with several other businessmen, helped organize and fund the group. Perhaps suspecting that Coogan’s intention was to receive its nomination for mayor, the group passed a by-law that none of its own members would be endorsed as candidates.

Rebuffed by the city’s elite, Coogan tried to make the best of it and turned to the working men of the city. Denouncing the Citizens’ Association as a tool of “capitalists,” he began courting the nomination of the Central Labor Union, a federation of city trade unions. Should the labor group offer their endorsement and nomination, he told them, he would personally put up $200,000 of his own money in support of the campaign (about $5 million in 2013 dollars.)

But James J. Coogan was a furniture man. At the boisterous nomination convention of the Central Labor Union in September, 1886, his few delegates were sharply and sarcastically shouted down by working men who had probably had dealings with Coogan, or others in the same business. In the final vote of the proceedings Coogan received just 31 votes of some 400 cast, with the vast majority of support for Henry George, the author of several pro-labor reform books.

Over the next two years Coogan apparently worked on his reputation among the laborers of the city for in 1888 he was enthusiastically given the nomination of the United Labor Party, cheered by many of the same delegates who had hissed him at the earlier convention. Coogan did not win the election of 1888, receiving about 10,000 votes that he estimated cost him roughly $10 each in campaign expenses. The winner that year was 30-year-old Hugh J. Grant, a Tammany Democrat who was (and still is) the youngest person ever to hold the office.

—

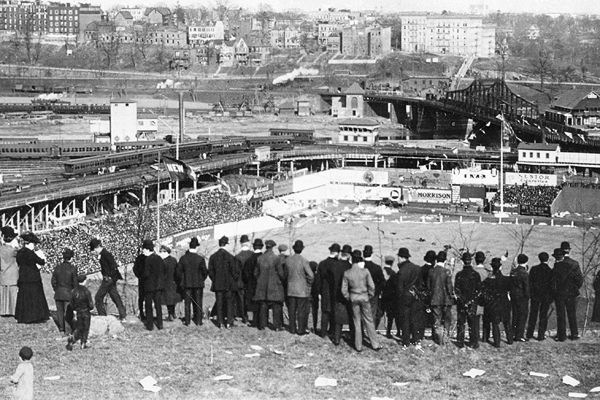

Much of the property Harriet Coogan would later inherit was in Hamilton Heights, including a long valley edged on the west by a high rock outcropping that came to be known as Coogan’s Bluff. In 1872 two new avenues were laid out in the area, one along the top of the bluff and one near its base. Unnamed at first, the avenues were mapped simply as “New Avenue West” and “New Avenue East.” By 1884 the upper avenue had come to be called Edgecombe Avenue for its location along the top of the bluff. By 1888 the lower avenue was referred to as Coogan Avenue, after James and Harriet Coogan.

Neither name was official, however, in that they had not been formally designated by the Board of Aldermen. This was certainly not uncommon in the history of Manhattan street names. Prior to the implementation of the Commissioners’ Plan in 1911, street names were often first designated by owners of the property through which they were opened and then later officially adopted (or not) by the city. It may have been James Coogan himself who first assigned the names. Despite their unofficial standing, the names obtained quasi-official status through common usage, published maps, and signage put up by the street department.

—

On the day after the mayoral election of 1888 it was discovered that someone presumedly in opposition to Coogan’s candidacy had removed all the street signs along Coogan Avenue. The matter was brought to the attention of the Board of Aldermen who looked back into the minutes and found no record that the name Coogan had ever been officially designated. On January 23rd 1889, on the motion of newly-elected Alderman John Carlin, the street was officially named Bradhurst Avenue after another nearby landowner, Dr. Samuel Bradhurst, thereby erasing the name of the failed candidate from the map.

There seems little doubt the renaming was politically motivated. Although Carlin was not a Tammany politician like Mayor Grant, he and the other Aldermen may have seen an opportunity to ingratiate themselves with the new mayor. (Carlin would go on to be associated closely with Jay Gould, supporting Gould’s plans to expand the city’s elevated railways.) The aldermen had also been made aware in 1889 that Edgecombe had never been named formally by the board, but saw no need to bestow an official name to the avenue until 1898 when it was extended past 155th Street.

As for James J. Coogan, he once again embraced his enemies in defeat as he had done the workingmen in 1886, and cultivated his friendship with Richard Croker, the leader of Tammany Hall. In 1899, after a decade of service to Croker, Coogan was rewarded by being elected President of what was now the Borough of Manhattan in the newly-consolidated City of New York.